With the jury still out on the most sustainable textiles, efforts to make the garment industry more sustainable are focusing on reducing consumption, reports Angeli Mehta

UK consumers buy more clothing per person than any other country in Europe – more than one million tonnes every year. Around 300,000 tonnes goes to landfill or is burnt, and less than 1% of fibres used to make garments are recycled into new clothing.

More of us may salve our consciences by taking used clothing to charity shops or recycling bins: according to WRAP, around 200,000 tonnes were sold for re-use in 2014, and 350,000 tonnes were exported. The poor quality of many garments means much of the clothing ends up in landfill in the developing world, suggests Tim Cooper, who leads research groups on sustainable consumption and sustainable clothing at Nottingham Trent University. There’s a particularly telling video online of women shredding clothes for recycling in India: they assume that water is so expensive in the industrial world that people can’t afford to wash their clothes, so discard them instead.

The garment sector has become a 'monstrous disposable industry'

Worldwide, the number of times clothes get used before being discarded has fallen 36% since 2012; in China the figure is 70%, according to a report for the Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

It has estimated that textiles production accounts for more carbon emissions than maritime shipping and international flights combined. Just the simple act of wearing garments for longer would cut emissions.

The garment sector has become a “monstrous disposable industry” thanks to the rapidity with which new designs are churned out in the world of fast fashion, according to British designer Phoebe English. She told a recent inquiry by the House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee that rather than make only what’s been ordered, the industry puts prospective sales into production, leading to countless wasted garments, not to mention the hundreds of thousands of tonnes of fabric left over in design and production.

It’s clear the fashion industry couldn’t be further from circularity.

“Slowing the cycles is as important as closing the loop. We need to build up markets for recycled material. But it only takes you so far,” says Cooper. “My problem is [that] … recycling perpetuates the throwaway culture, and it uses energy. The latest figures from the IPCC make clear we need to reduce consumption. We’ve got to go beyond efficiency and recycling to something more fundamental.”

WRAP estimates that companies across the garment supply chain could cut their carbon, water and waste impact by 3% if they made clothes that last just three months longer; nine months could improve that by up to 10%. Cooper and his team at Nottingham Trent University designed a protocol for WRAP to help designers and manufacturers create longer-lasting garments.

It’s quite hard to test garments properly for durability because there’s no time, there’s pressure from retailers to have turnover

Some brands have trialled the impact of machine washing on different hemming techniques to extend garment life, or developed new technical specifications to improve colour fastness or reduce pilling on knitwear – all potential means to encourage customers to wear garments for longer.

But Cooper concludes that “it’s quite hard to test garments properly for durability because there’s no time. There’s pressure from retailers to have a turnover of garments on display, plus customers don’t want things to last because they want change. Young people may wear something just once or twice.”

Swedish fashion group H&M has launched an online initiative to help consumers repair and look after their clothes, although it won’t comment on traffic to the site.

Peer-to-peer sales of used clothes are growing rapidly, thanks to online platforms like eBay, Vinted and Poshmark. US platform ThredUp received 21 million items from across North America last year, compared with 4 million in 2014. Research it commissioned suggests that if everyone in North America bought one used item instead of a new item, that would save over 200,000 tonnes of waste, and 2.6 million tonnes of carbon dioxide – the equivalent of taking half a million cars off the road for a year.

But why buy when you could rent? That’s the logic behind increasingly popular platforms like New York company Rent the Runway, UK-based Girl Meets Dress, or China’s Y Closet.

It is what you do with 1.2 million tonnes of fibre that the British industry uses collectively each year, and we need to work harder, all of us

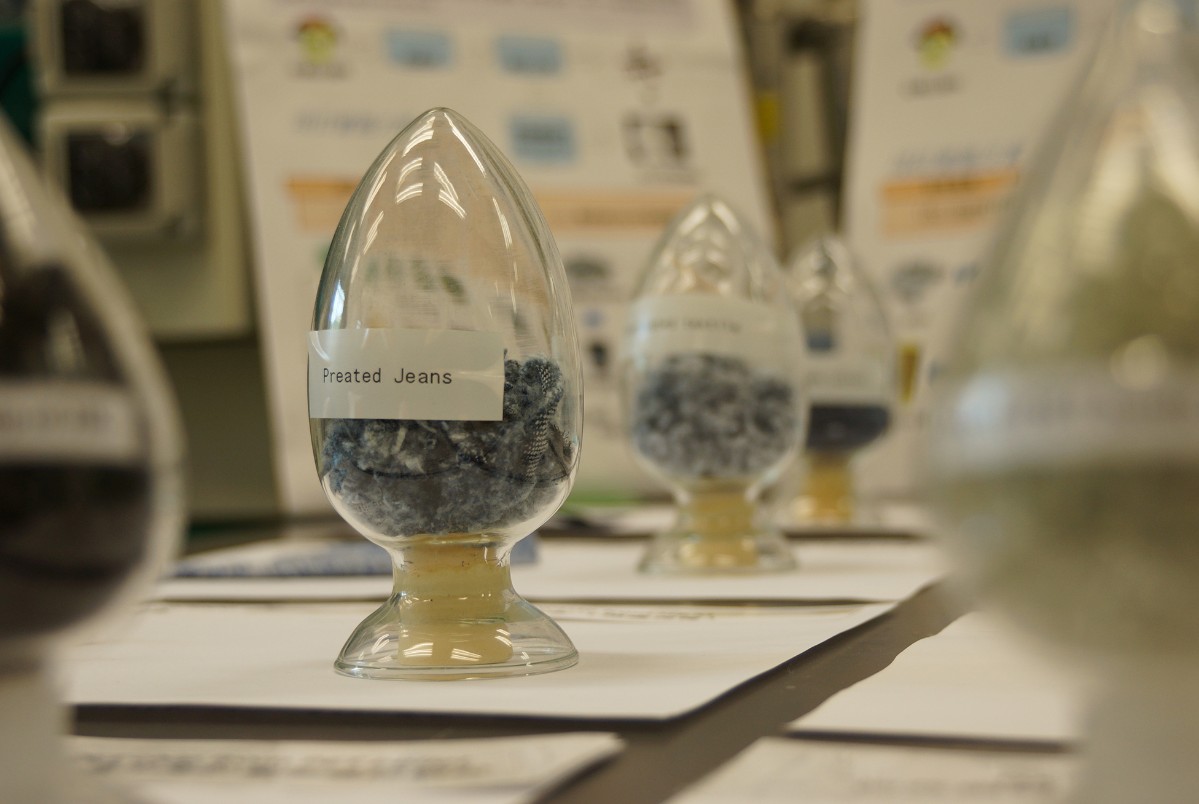

Netherlands-based Mud Jeans is trying to slow down the fashion cycle. Its jeans are made with reuse, repair, and recycling in mind, using techniques that recycle water and cut harmful chemicals. Consumers contract to return them at the end of use, or can even lease them.

If still wearable, jeans will be upcycled and sold again – indeed they sometimes come back in almost perfect condition, according to Eva Engelen, an engineer responsible for corporate social responsibility at the company.

To make the jeans recyclable, they’re as simple and “mono-material” as possible, says Engelen: there are no leather labels, and stainless steel buttons can be reused or recycled back into buttons.

Mud Jeans got its first batch of jeans back for recycling nearly four years ago, so garments now being sold consist of 23-40% recycled denim, blended with organic cotton. The search is on for chemical recycling techniques that will help cut that quantity of virgin cotton.

In the UK, M&S has been running a take-back scheme in conjunction with Oxfam since 2008. Mike Barry, director of sustainable business at M&S, told the Environmental Audit Committee that the challenge is not about take-back per se:

“It is what you do with 1.2 million tonnes of fibre that the British industry uses collectively each year, and we need to work harder, all of us, in terms of developing new industries that can use the fibres. It is quite possible to prevent anything going to landfill or to incineration. It is much harder at the moment to do something with the fibres you recover”.

We have taken suits back and reused them, but it is more to raise awareness of the issue

M&S does have an ambitious voluntary target for 25% recycled fibre content across 25% of its clothing by 2025. The committee heard that M&S had made a men’s suit line with 50% of the wool recovered from the take-back scheme. “We have taken suits back and reused them, but it is more to raise awareness of the issue rather than to claim that it is hundreds of thousands of garments. It is not,” Barry says.

Both H&M and its charitable foundation have invested in a range of promising recycling technologies, but these need to get to scale. In 2018, H&M used just 1.4% of recycled materials, including cotton, polyester from plastic bottles, nylon, wools, silver and down. A swimwear range, for example, uses Econyl’s regenerated nylon, made from fishing nets and other nylon waste.

There are multiple challenges in recycling, including separating fibre blends in textiles, and ensuring fibres maintain their properties.

H&M Foundation is funding a four-year €5.8m partnership with the Hong Kong Research Institute of Textiles and Apparel (HKRITA), which has developed three recycling techniques. One of these – a mechanical approach – is now processing three tonnes of unwanted textiles into yarn each day at Hong Kong yarn producer Novetex. It plans to scale to 10 tonnes per day. Textiles woven with the recycled yarn will have about 30% virgin fibre added, but the fibres can be recycled again. H&M is one of the first customers.

Novetex’s yarns will be made into textiles in China. China’s ban on waste imports – including textiles – means solutions, like those of HKRITA, are urgently required in the markets where waste originates. Hong Kong government figures show that Hong Kong consumers alone send 247 tonnes of textiles to landfill every day.

The institute’s other recycling processes are just as promising, says business development director Yan Chan: a hydrothermal method to separate polyester and cotton mixtures has been shown to work at pilot scale, and is expected to start commercialisation later this year.

When we design the materials we use, we can think about recycling at the end – and not just once

Chan is optimistic about the prospect of a circular economy: thousands of visitors from across the textile supply chain have already beaten a path to HKRITA’s door. “When we design the materials we use, we can think about recycling at the end – and not just once.”

The partners have also set up a garment-to-garment recycling demonstrator where customers can bring their unwanted clothes and watch the miniaturised system create new garments, to be sold. At its launch last year, Eric Bang, innovation lead at H&M Foundation, said “seeing is believing, and when customers see with their own eyes what a valuable resource garments at end-of-life can be, they can also believe in recycling and recognise the difference their actions can make.”

In the UK, Worn Again Technologies has raised the £5m it needs to take its dual polyester and cotton recycling technology out of the lab. The aim is to displace oil derivatives as the raw materials for polyester, and to cut the amount of virgin cotton going into clothing. The cellulose fibres produced in the process have many similar properties to cotton, and the industry is used to working with cellulose fibres to make viscose and Lyocell, for example. As chief executive Cyndi Rhoades, has pointed out: “There are enough textiles and plastic bottles ‘above ground’ and in circulation today to meet our annual demand for raw materials to make new clothing and textiles.”

IKEA, GAP, Adidas and H&M are among the signatories to the Textile Exchange’s recycled polyester commitment to grow their use of the recycled plastic by 25% by 2020: a target they’ve already exceeded. In just a year, their combined use of recycled polyester – or rPET – was up 36%. But with fibre-recycling technologies only beginning to emerge, plastic bottles are the main source material.

So, could synthetic fibres be one answer to a more circular textiles industry? Cooper says more research is needed. “We’re still utterly lost about best practice. All [fibres] have problems,” he says, warning that switching from synthetic to natural fibres may have unintended consequences. The shedding of microfibres joins a long list of issues that need to be tackled: water consumption; pesticides use; chemicals used in processing and finishes and how these are preserved in recycled fibres; and the difficulties of separating fibre mixes.

The UK has a voluntary Sustainable Clothing Action Plan (SCAP) co-ordinated by WRAP. So far, there are 80 signatories, accounting for about 60% of retailers by volume. While they have made progress on water consumption (down 10%) and cutting carbon emissions (down 13.5%), waste reduction across the supply chain has been cut by less than 1% since 2012, which suggests voluntary measures are not enough.

The Environmental Audit Committee concluded that brands and retailers should pay 1p per garment they create

The Environmental Audit Committee concluded that brands and retailers should pay 1p per garment they create, which would raise £35m to invest in clothing collection. It also wants the government to investigate whether textile products containing less than 50% recycled PET should be taxed, and for it to consult on an extended producer responsibility (EPR) scheme for textiles by the end of the current parliament. The EU’s Circular Economy Package requires member states to extend separate collection requirements to textiles by 2025: Defra says it’s considering what can be done in the UK.

France has an EPR scheme for 19 different waste streams, including textiles: anyone putting textiles on the market has to contribute to recycling and treatment of the resulting textile waste. Since the law was introduced in 2007, the proportion of used textiles and clothing diverted from landfill has doubled – but significant quantities still end up there. Further measures were proposed last year: including banning brands and retailers from burning or landfilling unsold stock, and offering tax breaks to companies that sort textiles for re-use and recycling. A recent Swedish research programme concluded that an EPR scheme would have a big impact on both textile recycling and fibre-to-fibre recycling of used textiles.

The aim of the EU’s Ecodesign Directive was to increase the energy efficiency of products, and get rid of the least efficient. Now efforts are under way to improve material efficiency by considering durability, and recyclability. Could the approach work for textiles? Clothing labels don’t usually even give information on re-use or recycling. However, a report for the Nordic Council of Ministers details potential requirements for an ecodesign label for textiles and furniture.

These could include minimum recycled content; durability of fasteners, availability of spare parts (like buttons), design for disassembly or re-use – for example, the easy removal of logos. Cooper points out that creating a lifetime label for textiles is much harder than for electrical goods, but a voluntary code could signal durability – a gold or silver rating to indicate a garment has had a wash test or performance check might start to signal to consumers that longevity is something to consider.

In the UK, Defra says it intends to introduce ecolabelling for white goods, after EU exit, and that this could be extended to textiles.

As anyone in the fashion industry knows, trends quickly change. Consider the impact The Blue Planet had on consumer attitudes to plastics. What’s needed is a similar wake-up call to the dangers of fashion’s throwaway culture.

Angeli Mehta is a former BBC current affairs producer, with a research PhD. She now writes about science, and has a particular interest in the environment and sustainability. @AngeliMehta.

This article is part of the in-depth Circular economy briefing. See also:

To rise to the climate emergency we have to turn off the tap on waste

From refilling and sharing to recyclable thin film: the cutting edge on circular

Virginie Helias: P&G’s ocean plastic bottles ‘only the beginning’ of war on plastic

Australian university pioneers urban mining ‘microfactories’

The battle to turn the tide on the e-waste epidemic

Tata’s push to reinforce steel’s circular economy credentials

‘Companies aren’t moving fast enough on the circular economy’