Cranfield’s professor of corporate responsibility gives his personal view on how business schools have developed corporate responsibility programmes, and where their future focus should be

Twenty years ago, as one of the managing directors of Business in the Community, the UK-based, business-led coalition promoting corporate responsibility, I visited the Harvard Business School (HBS), to suggest it should teach corporate responsibility. My rationale was that if HBS took the lead, other business schools would quickly follow. And, that with the fall of communism, it would be prudent to develop theory and practice about responsible capitalism. My host listened politely, gave me a pleasant lunch in the faculty dining room – and sent me on my way.

Undaunted and shamelessly borrowing from the title of a 1980s business best-seller, I gave a lecture a few months later at Durham University Business School, entitled, “What they should teach you at Harvard and other business schools too”. I argued that what was then called corporate citizenship or corporate community involvement should be part of the business school curriculum.

I was invited to work with Chris Marsden, then at BP, to examine how to influence the business schools, and this led, in due course, to BP’s sponsorship of a corporate citizenship unit at Warwick Business School, in 1997.

Others had been following parallel tracks. The Co-operative Bank sponsored a chair in corporate responsibility at Manchester in 1992; Ashridge began its “business and society” project in 1993. By the turn of the millennium there was enough of a groundswell, for Étienne Davignon – as president of CSR Europe – to persuade a number of business school deans and international companies to launch Eabis – originally the European Academy for Business in Society (since 2010, the “European” descriptor has been dropped to reflect its increasingly global membership).

So when, in 2006, I was encouraged to throw my hat in the ring for the directorship of a new centre for corporate responsibility at Cranfield School of Management, I needed little persuasion – while doubting that a practitioner/campaigner like myself would be appointed.

I describe this personal odyssey solely to emphasise that changing the business schools is not a quick fix, or for the faint-hearted.

Some people ask me why it is so important. Do business people really listen to business school professors? Aren’t the global management consultancies and business media far more influential with business?

Millions of MBAs

There are more than 13,000 business schools in the world today, according to one of the leading accreditation bodies. In the next decade, the US schools alone will produce more than a million MBAs. Globally, some estimate three million new MBAs in the next 10 years. Many more will acquire other specialist business masters’ qualifications. The leading international schools also have thriving executive education programmes – providing both customised, in-company and open programmes for middle to senior managers – often including board-level workshops and experiential learning.

Many business school faculties consult with companies – either on their own account, or on behalf of their schools. Through books, articles in popular management journals such as Harvard Business Review and Management Today, speeches to trade associations and other management conferences, leading business school academics reach many more people than just those who study at the institutions where those academics are based. For good or ill, business schools and the prevailing ideologies taught across the world’s schools have a profound impact on managers and on the practice of management.

I don’t imagine for a millisecond that any business school dean, any faculty member, any business school advisory council member wants that influence to be malign. What has struck me very forcibly, however, in the nearly five years since joining academia, is the degree of angst and soul-searching that is going on in the world’s business schools. Writing in a recent edition of the Financial Times, Morgan Witzel of Essex Business School says: “The credibility of business schools as institutions, indeed their very future, is at stake.”

I listened recently to the very thoughtful new dean of Insead, Dipak C Jain, who observed that “what has gone wrong is that business schools have put performance before purpose,” and that in future, business schools’ purpose should be “from success to significance”.

There are a number of organisations and initiatives trying to help business schools to rethink their purpose and modus vivendi, such as the UN’s Principles of Management Education (PRME, a UN Global Compact for the world’s business schools) and Eabis.

A group of academic staff from schools across the world initiated a Global Responsible Leadership Initiative, which is now examining what the business school of the future should be. In the UK, the Higher Education Funding Council has sponsored an investigation by Nottingham, Warwick and Bath Business Schools, to examine what is happening about sustainability and responsibility in the UK’s 100-plus business schools.

These are welcome developments – but as yet, between them all, they are only involving a fraction of the 13,000 business schools or the maybe 330,000-plus business school faculty, across the globe.

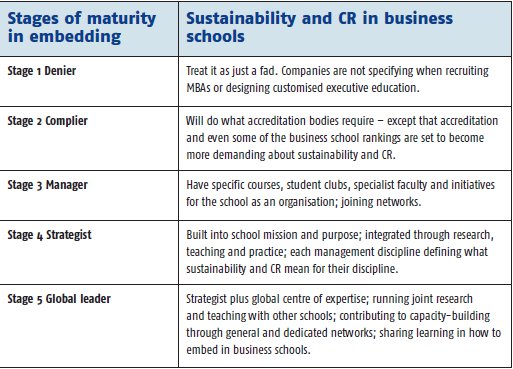

Academics and practitioners frequently talk of businesses being at different stages of corporate responsibility maturity. One might apply a similar logic to business schools’ maturity on sustainability and corporate responsibility.

Just as we encourage companies’ boards and senior management teams to ask themselves three questions, so business schools might ask:

· Where on the stages of maturity are we today?

· Where do we aspire to be in future?

· What will we need to do, in order to get from today to where we want to be, and crucially, who will be accountable for different elements of the action plan?

Careful paths

Like each company that has to map its own journey, business schools will do so based on their culture; faculty perspectives and focus; student, alumni and business partner interests; and wider university resources (where appropriate). Business schools are no more homogenous than businesses are and, therefore, there are no silver-bullet, one-size-fits-all solutions.

Just as with businesses, the starting point needs to be for individual schools to decide for themselves what their purpose is. Smart schools will make that an inclusive enquiry involving current and former students, business and community partners, benefactors and staff, as well as faculty at all levels. Then, just as businesses need to embed sustainability and responsibility in all they do, so schools need to consider the implications for their research, teaching and consulting/practice – and in their own conduct as an employer, customer, supplier, neighbour, and as wise stewards of their resources for the future.

The UN PRME website includes reports of how signatory schools around the world are going about this process, given their own distinctive cultures, histories and traditions.

Levers for change

From my own past life as a campaigner and social entrepreneur, I do see a number of potential levers of change, which might speed things up.

Just as many of the companies most advanced on the sustainability journey have learnt the importance of combining top-down leadership and strategic direction with the creativity and dynamism of bottom-up engagement, so the business schools would do well to listen to their students.

In many cases, it is the students who are ahead of the schools in seeing the importance of these issues for their future careers – and for the state of the world in which they hope to bring up families.

Most business schools provide funds for their faculty to attend academic conferences each year, to present their research and to keep up to date with the latest academic thinking. Perhaps over the next five years, each faculty member should be encouraged to divert sufficient of their conference budget to enable each to attend and to learn from at least one student-organised sustainability conference, such as Net Impact in the US, or IESE’s Doing Good and Doing Well in Barcelona, or the Being Globally Responsible Conference organised at the China Europe International Business School in Shanghai each year.

Students with an interest in these issues are already helping faculty members to produce new teaching cases with an emphasis on sustainability and responsibility. In the UK, the Pears Foundation has created a business school partnership with London, Oxford and Cranfield to generate 27 new teaching cases over three years, examining how successful individuals can contribute to the public good in different ways.

Business schools spend a lot of time worrying about their rankings and their accreditations. Both those producing the rankings (such as the Economist, the Financial Times, Business Week among others) and those in charge of business school accreditation (EQUIS, AMBA, AACSB etc) could have a profound impact simply by announcing that how well a school embeds sustainability and responsibility will henceforth be part of rankings and accreditation.

There is one group that has a particularly influential voice if they choose to use it – and which might be expected to have a particular stake in persuading the business schools to change: business. I have heard many business school professors with far longer and wider experience than mine opine that the mass of business schools will only really change when business customers insist upon it. That may be a little too simplistic – but corporate leaders should certainly stop grandstanding that “business schools need to do more about CR and sustainability” and start using their undoubted power to incentivise schools to change.

Here are six things that readers of Ethical Corporation could lobby their companies to do. Companies that care can help corporate responsibility and sustainability “occupy” business schools in the following ways:

1. Open doors to business schools to research, and write teaching cases about their challenges in embedding corporate responsibility and sustainability and how they are going about this. The world’s largest mobile phone business China Mobile is doing just this.

2. Collaborate with other companies to offer mentoring and privileged research access to bright younger faculty members, wanting to make their academic names with relevant and rigorous research around corporate responsibility and sustainability.

3. Communicate expectations to business school careers services and MBA/MSc course directors that graduate recruits have a good understanding of how to manage ESG (environment, social and governance) factors in the business (both as risk mitigation and opportunity maximisation). All too often, right now, the signals corporate recruiters are sending to business schools are just the opposite.

4. Unite business school alumni in the company who are interested in corporate responsibility and sustainability in becoming activists, pressing their schools to take these issues more seriously – if for no other reason than because not to do so may devalue their own qualifications from that school in the years to come.

5. Plan top talent development and executive learning programmes to achieve sustainability and responsibility learning outcomes. Specify this is part of what companies are commissioning. Again, executive education directors in business schools say this is not the general message now.

6. Yield old ideas to new dialogue. Provide senior leaders from the company to speak on business school campuses, where they can weave in ideas about ESG performance as an integral part of their narratives. But make it clear to the schools: if your CEO or senior executive director is speaking on campus, you expect faculty members as well as students to attend.

Alert readers will notice I have not suggested anything here that has a budget request attached. This is not to say that individual, corporate or foundation sponsors interested in speeding up the transformation of business schools to become agents of responsible management and managing for sustainable development could not make strategically valuable interventions. For example, to teach high-flying younger faculty members from different business schools how to improve the teaching of these topics; or to incentive cross-disciplinary management research (something which the current focus of writing principally for three and four star academic journals militates against).

Above all, we need to inspire business school faculties to engage in the debate about just what business schools are for.

David Grayson is the Doughty professor of corporate responsibility at Cranfield School of Management and a member of the Ethical Corporation editorial advisory board. He writes here in a personal capacity.