A surge in corporate no-deforestation commitment hasn’t stemmed habitat destruction in Indonesia, as a new report by RAN on illegal deforestation in Sumatra highlights. We assess whether a new methodology for implementing them called the High Carbon Stock Approach could help turn the tide

Corporate commitments to end deforestation caused by palm oil have multiplied in recent years amid increasing investor and consumer concern about growing demand for this cheap commodity, found in about half of consumer products, from bread and breakfast cereals, to household detergents and cosmetics. It is also being used in biofuels and power plants.

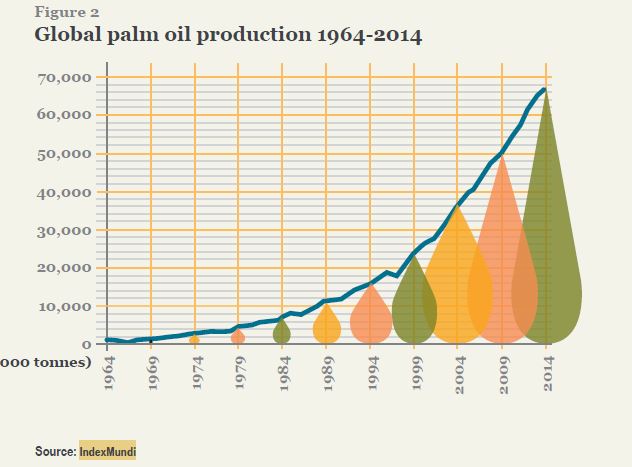

Global production has doubled over the past decade, expanding more rapidly than almost any other agricultural commodity, according to Ceres in a new investor brief on palm oil. And annual demand is expected to grow another 50% to 77 million tonnes in 2050. The “rapid and poorly managed” expansion is causing massive large-scale deforestation and significant greenhouse gas emissions from clearcutting and burning tropical forests, Ceres’s Engage the Chain report points out. Indonesia, the biggest palm oil producer, has lost an area almost the size of Germany since 1990.

Not only are the forests that provide ecosystem services such as water, food, and fuel to indigenous communities being destroyed, smoke and haze from the clearcutting and burning blanket much of South East Asia for months on end, with serious health consequences, the report says. It is also having a devastating impact on biodiversity, particularly the endangered Sumatran Tiger, with 43% of the Tesso Nilo National Park in Sumatra over-run by illegal palm oil plantings.

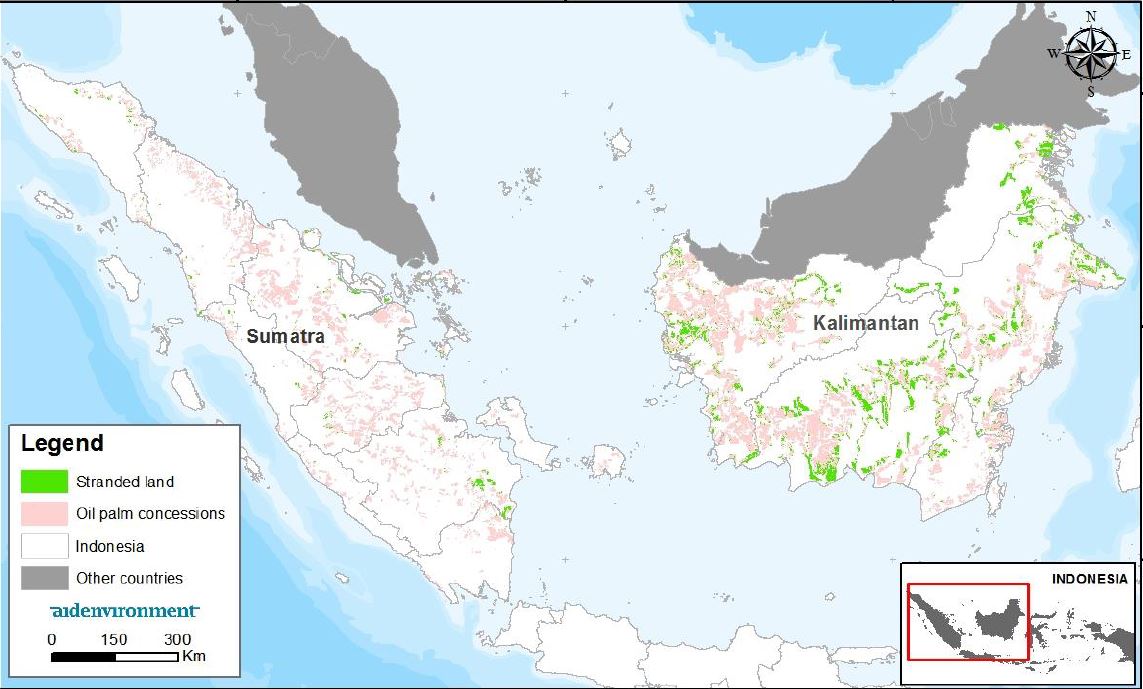

According to research from Washington-based Chain Reaction Research, there are now 365 companies with No Deforestation, No Peatland, No Exploitation policies. It calculates that 29% of Indonesia’s leased out landbank, an area equal in size to 10 million football fields, risks becoming stranded assets if buyers’ no deforestation policies are implemented.

Curbing deforestation

But the big question is whether these no-deforestation policies are actually stemming the destruction of forest and peatland. A scorecard of the biggest companies’ deforestation-free commitments by Greenpeace last year found that only two of 14 companies surveyed, Ferrero, maker of Nutella, and Nestle, are on track to meet their commitments, and only Ferrero can trace nearly 100% of its palm oil to the plantation where it was grown. (According to Ferrero 100% of its palm oil can now be traced) Unilever, the world’s largest purchaser of palm oil, only scored “decent” marks for responsible sourcing and transparency.

“Our analysis shows that companies have yet to take control of their supply chains and are unable to say with any confidence that the palm oil they use is not driving the destruction of rainforests, threatening endangered species or contributing to social conflicts in Indonesia,” Greenpeace said.

A hard-hitting new report by the Rainforest Action Network this month, meanwhile, highlighted the risks for brands from a single deforestation event far down in their supply chains. It said no deforestation policies from some of the world's major brands, including General Mills; Kraft Heinz; Kellogg Company; Mars; Mondelez; Nestlé; PepsiCo; Unilever; McDonald’s; and Procter & Gamble, “aren’t worth the paper they’re written on” because of their association with illegal deforestation in the Leuser ecosystem in Sumatra, home to the largest remaining populations of the Sumatran tiger, Sumatran elephant, Sumatran rhino and the Sumatran orangutan.

This is because the brands source from large palm oil traders, including Wilmar, Musim Mas, Golden Agri Resources, and Cargill, which RAN says have failed to take the "corrective action" they have promised since 2014, when RAN first highlighted illegal clear cutting by one palm oil supplier, PT Agra Bumi Niaga. RAN produced satellite images showing that the area in its concession covered by forests had reduced from 420 hectares in June 2016 to 88 hectares in April 2017.

"Major brands continue to hide behind corporate greenwash while forests are flattened in the Leuser ecosystem to make way for conflict palm oil plantations,” RAN concluded.

A lack of unity

Simon Lord, group chief sustainability officer for Malaysia-based Sime Darby, the world’s biggest producer of certified sustainable palm oil, which was not named in the RAN report, told Ethical Corporation that some of the palm oil traders named, including Wilmar and Musim Mas, are the ones that are working hardest to make palm oil sustainable. "It's always the same names that are attacked. … The ones who are trying to make a difference. The ones who are most transparent. Because by trying to live up to standards that are above the industry norm we expose ourselves and time and time again we get hit."

Wilmar, which controls 45% of the global palm oil trade, said last year that it had made “significant progress” on its 2013 commitment to eliminate deforestation, exploitation and peatland development from its supply chain, including publishing a list of crude palm oil mill sources that supply its refineries. However Wilmar’s chief sustainability officer, Jeremy Goon, also pointed out that “much remains to be done, including the development of a clear means to measure and track the progress of sustainability commitments to assess its effectiveness in reducing actual deforestation”.

Lord agrees that the lack of a single methodology supported by both NGOs and companies until now has made it difficult for brands to take action to remove deforestation risks from their palm oil supply chains. Buying palm oil certified by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil is no guarantee since its rules mainly cover undisturbed primary forest, of which there is little remaining in Indonesia. Most of the plantation concessions are instead on fragmented landscapes of secondary forest that are in various stages of regeneration.

In the absence of strong rules from the RSPO, two alternative methodologies evolved, with big differences on what secondary forest should be protected, either because of their carbon and biodiversity value or their value to indigenous communities.

A stalemate between two competing approaches was resolved late last year, after Sime Darby and Unilever brought leading industry players and NGOs together in a series of workshops to agree a converged High Carbon Stock (HCS) Approach to assessing forests, and released a toolkit in May guiding companies on how to implement them.

Adita Sen, climate and sustainability advisor for Oxfam in the US, which was an observer but not participant in the development of the High Carbon Stock Approach, describes it as "an important step forward. … Companies now have the methodological clarity they need to start moving toward deforestation-free supply chains."

One caveat is that while the methodology gives primacy to the issue of land rights and free and prior informed consent by affected communities, it remains to seen whether indigenous communities will truly be brought into the decision-making process. Oxfam would also like to see pathways to enhance the livelihoods of small-scale palm oil farmers.

Lord says when more companies begin implementing their commitments using the HCS Approach, even more of companies’ palm oil concessions, awarded by the Indonesian government, will be out of bounds because they will not be able to develop them sustainably. This is the case with Sime Darby’s 220,000 hectare palm oil concession in Liberia, where the new approach will not allow the company to lift a moratorium on planting it imposed on itself in 2014.

Revoked land

But here’s the rub: a key point in the Chain Reaction report is that compliance with no deforestation commitments is no guarantee that forest and peatland will be protected. This is because under current government of Indonesia regulation, growers’ licenses can be revoked after three years if they do not develop their land into palm oil plantations. “Licenses can then be redistributed to other actors, including those active in other commodity sectors that are not necessarily bound by any NDPE policy,” the report points out.

Lord confirms that the Indonesian government has exercised this right. “Several large companies I know about have had high carbon value areas taken away from them and given to other companies. … It's always a threat.”

Besides palm oil, the land could also be awarded for rubber plantations, a commodity that is almost as ubiquitous as palm oil in south-east Asia (covering about 70% of the acreage covered by palm), according to researchers from the University of East Anglia’s School of Environmental Sciences. As Ethical Corporation reported last year, among tyre makers, the biggest users of rubber, only Michelin has committed to a deforestation-free supply chain.

Gabriel Thoumi, director of capital markets at New York-based Climate Advisers, and one of the authors of the Chain Reaction report, says many small and mid-sized Malaysian companies have both palm and rubber plantations, and overlapping boards.

He points to an additional problem: while deforestation-free commitments bind individual companies, joint ventures, even between two companies that have individually made zero-deforestation commitments are not covered. “There’s a gaping hole in the NPDE in that it doesn’t cover joint ventures, and in some cases a significant amount of revenue is coming to the companies from their joint venture sales.”

PepsiCo ‘not serious’

One high-profile case with Malaysia's IOI, which was suspended from the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil last year after a complaint by Dutch NGO Aidenvironment, leading major multinationals, including Unilever, Kellogg’s and Mars, to drop IOI Group as an approved supplier.

But the more egregious example is PepsiCo, whose heightened palm oil commitment, made in 2015, specifically exempts its joint venture partner Indofood from adhering to its heightened social and environmental standards.

Indofood, which produces PepsiCo products in Indonesia, is Indonesia’s third-largest private palm oil company and the last company among the top three palm oil growers yet to adopt a responsible palm oil policy.

Eric Wakken of Aidenvironment, the Dutch NGO that forced the RSPO to sanction IOI and authored the RAN research on Indofood, says PepsiCo has shown it isn’t serious about its no-deforestation commitment by letting Indofood off the hook.

“IndoFood continues to carry out peatland conversion. They aren’t engaging with civil society or [palm oil] buyers in a positive way. …. Usually plantation growers will surrender [when they come under pressure] but others, like Indofood, are focused on the Indonesian market and have less interest in being part of the international market.”

Wakken says NGOs like Rainforest Action Network and Greenpeace will keep up the pressure on PepsiCo and other companies like South Korea’s Daewoo, Korindo and Nobel for sourcing what they call “conflict palm oil”.

But despite such leakages, he believes the no-deforestation movement is "like a tanker that will not be turned around".

“NGOs have been successful in pressing the palm oil industry to commit to end deforestation and peatland conversion even though the Indonesian government had allowed that type of development,” he says. “I think we are slowing deforestation down, but it’s hard to demonstrate right now as the policies have only been in force for three and a half years.”

Positive impact

Even if the Indonesian government does withdraw the licences of palm oil companies that are sitting on stranded assets and give them to companies without deforestation commitments, he says the market for commodities linked to deforestation is shrinking, even in Asian markets.

“No large international brand wants to be associated with deforestation anymore,” Wakken says. “We estimate that two thirds of all palm oil refineries in the world are owned by companies with no-deforestation commitments.”

Meanwhile, palm oil companies want to show that they can actually have a positive impact on declining species. Sime Darby is one of a group of palm oil growers, including Musim Mas, Wilmar, PT ANJ Agri and United Plantation Bhd, that has formed an alliance with conservation NGOs called the Palm Oil and NGO Alliance (Pongo, for short).

Part of its remit is to prevent the estimated 10,000 orangutans who currently live on non-certified palm oil concessions, mainly on the island of Borneo, from becoming extinct if their habitats are not managed properly. This would turn the 20,000 hectares of palm oil stranded assets into conservation sites, and presumably make it more difficult for the Indonesian government to revoke their licenses.

Wakken says the Indonesian government should listen to the no-deforestation message from the market. “It’s time the government takes it [the High Carbon Stock Approach] into its land-use planning.”

This article is part of a package on deforestation in global supply chains. See also: