Oliver Balch talks to Leon Wijnands, head of sustainability at the Dutch bank, about how his team developed the Terra approach, a ground-breaking methodology he hopes all banks will adopt to steer climate-friendly lending

Leon Wijnands likes to tell people he lives 3.8 meters below sea level. Then he tells them that his home town of Almere was, until not so long ago, actually under water.

“I say this so people understand that I have a personal interest in the effects of climate change,” says the 54-year-old Dutchman.

The relevance of increasing temperatures and rising sea levels hasn’t always preoccupied Wijnands. Indeed, when his bosses at the Netherlands-based bank ING first sounded him out about his current role as head of sustainability, he figured it was something “you do alongside a real job”.

In late 2015 came the Paris Agreement and the whole landscape for banking changed

It didn’t take him long to change his view. When he took up the post back in October 2013, ING’s energy-related loan book weighed heavily in favour of oil, gas and coal, a point highlighted by Oxfam and Greenpeace in a 2017 complaint to the OECD.

But moves were afoot to change. Talk of climate-related liabilities and “stranded assets” were already taking hold inside ING, one of the “big four” in the Dutch banking sector. Then, in late 2015, came the Paris Agreement and the whole landscape for banking changed.

Article C of the landmark agreement calls on banks to ensure finance flows in line with the two-degree pathway agreed by world leaders. In light of this key clause, Wijnands sat down with his internal team of a dozen or so sustainability experts to assess the carbon footprint of ING’s existing loan portfolio.

It didn’t take long before they ran into hurdles. The first centred on the availability of data. Company reporting on carbon emissions and related risks remains sketchy at best. Wijnands’s team weren’t alone in their hunt for hard, comparable numbers. It was precisely the same scramble in the dark that led G20 leaders to set up the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures four years ago.

Then came what Wijnands defines as the “attribution challenge”, by which he means the proportion of a company’s emissions that land at ING’s door. For investors, it’s relatively easy. You have a 2% share in a company, he says, you accept 2% of that company’s emissions as yours.

“But in lending, if you deal with a syndicate of 10 banks, plus an export facility for six months, say, what part of the footprint do you allocate to that lending product? And if next to that product you have a revolving corporate facility with that client, how do you avoid double counting?”

Wijnands was assigned 'a hipster, a hacker and a hustler' to resolve what a Paris-aligned financing strategy should look like

It was a “Houston-we-have-a-problem” moment, he recalls. Stumped on both fronts, Wijnands went looking for help. But rather than turn to an external consultancy, he put in a call to an internal team within ING that deals with just such knotty innovation challenges.

The way it works in ING is that a call goes out to the bank’s 54,000 employees laying out the challenge. Anyone interested in having a crack at it is invited to apply for a short secondment.

That’s how, towards the end of 2017, Wijnands ended up being assigned “a hipster, a hacker and a hustler” (read: someone from the IT, finance, and wholesale banking divisions, respectively). Their task: to resolve what a Paris-aligned financing strategy should actually look like.

ING’s sustainability director gave the trouble-shooting trio carte blanche, something he almost immediately regretted, he recalls laughingly.

“They questioned everything, absolutely everything. Nothing we had developed was good enough, it seemed . . . over and over again, they would ask ‘why this, why that?’ They were really quite annoying and irritating people [but] thus is really what you need if you want radical change.”

Such tensions are par for the course. The methodology encouraged by ING’s internal innovation office actively encourages team members to diverge. This applies equally to individual members of the team, as it does any and all previously accepted assumptions, norms and ideas.

The chief conclusion of the in-house, problem-solving effort was the idea that there is 'not one road to Paris'

In this way, the bank’s appointed team of innovators are able to avoid tunnel vision, Wijnands explains. The idea is, of course, that they all eventually re-converge. And, when they do, both problem and solution are that much clearer.

For all his tongue-in-cheek complaints, Wijnands insists that the eight-month process, which resulted in the publication of ING’s Terra approach last year, was worth all the personal and professional frustration.

The chief conclusion of the in-house, problem-solving effort was the idea that there is “not one road to Paris”, as Wijnands puts it. Every country, every industry sector, every individual business, needs to determine its own route to limiting global temperatures to 1.5 or 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

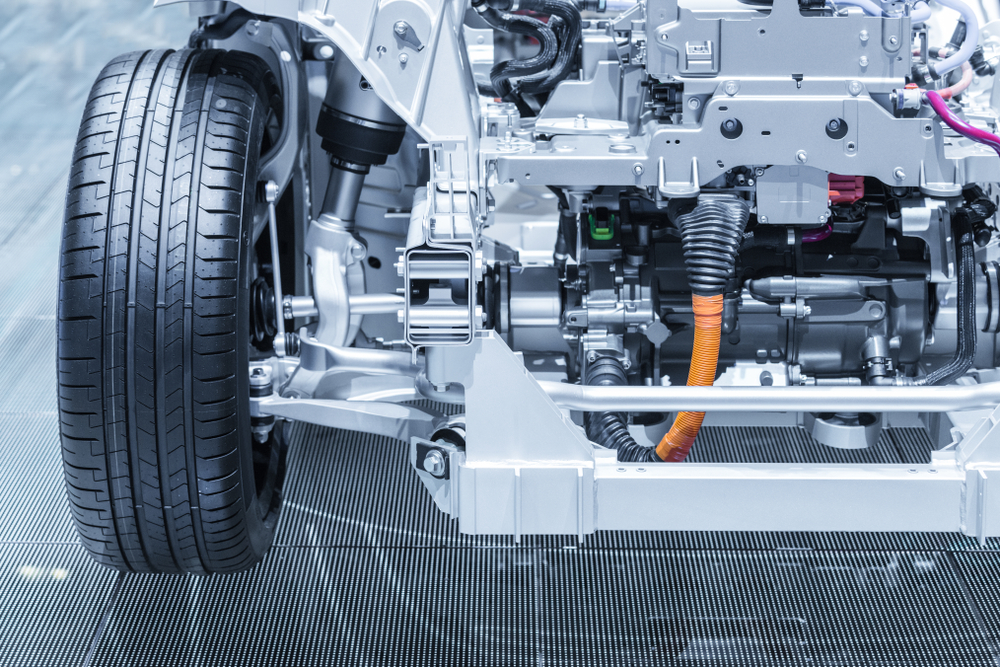

For ING going forward, this means a more sectoral approach to analysing its climate-related portfolio risks and opportunities. Its chief focus will be given to corporate lending – both past and future – in carbon-intensive industries: namely energy, automotive, shipping and aviation, steel, cement, residential mortgages, and commercial real estate.

Another insight incorporated into ING’s new Terra approach is the crucial role of technology in the low-carbon transition. Helping to steer tomorrow’s technology mix is where banks come in, says Wijnands.

ING has been developing a suite of new evaluation tools to support its new lending strategy, including a recently launched “energy robot”. This web-based tool shows the bank’s real estate clients what technologies will help ensure their individual properties meet required eco-efficiency ratings.

Banks should focus most on where they can make a positive difference, not on where they can avoid the most harm

One implication of this focus on technology is that banks should, perhaps, sweat a little less about the precise ecological footprint of their loan portfolios. That’s not to say that they shouldn’t continue trying to calculate their direct and indirect carbon emissions. Nor does it imply stopping the environmental screening of future clients. Both are steps that ING remains deeply committed to, Wijnands insists.

His point, instead, is one of prioritisation. Banks, he says, should focus most on where they can make the most positive difference, not on where they can avoid the most harm. “Society is not going to change as a result of what we don’t finance,” his basic logic runs. “Society is only going to change as a result of what we do finance.”

ING, needless to say, is not a technology company. For its approach to be successful, its clients need to join it in pushing forward technological solutions to climate mitigation and adaption. As well as robots and the like, ING has also been exploring product innovations that might incentivise such a shift.

Wijnands cites a sustainability improvement loan developed by the bank’s wholesale division. A first for the syndicated loan market, the product essentially promises a lower credit rate to companies that improve their sustainability performance.

He is characteristically candid about the relationship between the Terra approach developed by his team and the suite of product innovations and measurement tools created by other sections of the bank.

“Bringing all the various initiatives that are already developed or still under development under the same umbrella gives us a much more coherent approach. But it would be too much to say, ‘Well, this is how we designed it three years ago and then this is how we set everything up.’ No, it's been a more organic, incremental way of thinking than that.”

What it means for a bank to follow a 'two-degree pathway' is still, in large part, anyone’s guess

Such candidness is not only refreshing, but instructive. What it means for a bank to follow a “two-degree pathway” is still, in large part, anyone’s guess. Despite a slew of industry initiatives, as many questions remain as answers.

Wijnands acknowledges this. Not having a background in sustainability (sales and customer services account for the bulk of his career) he makes no bones about not having all the answers. Hence his willingness to turn to others for help.

He asked the 2° Investing Initiative (2°ii), a non-profit thinktank, for assistance with the data challenges highlighted above. Not only does 2°ii already have tools in place for collecting and analysing climate-related data for corporate assets and services, it also specialises in measuring the potential financial risks of financial portfolios.

In the same spirit of partnership, Wijnands hopes the Terra approach will become a market standard. That means working with other banks to “co-create” (one of his favourite words) solutions to both the technical and strategic challenges associated with climate-friendly lending.

To that end, ING went public with a “charcoal draft” version of its Terra approach last September, at the Global Climate Action Summit in California. It was an unusual step, he admits. Normally, banks don’t publish anything until it’s “completely finished, triple checked … and has the blessing of the Pope”.

Going public without all the “I’s dotted was essential to getting other banks on board, he says. Creating a market standard from the Terra approach is only possible if it is seen as a working document open to the input of others: “If it's already seen as an ING approach, then other banks will say, ‘We will go and develop something on our own because apparently all the decisions are already made’.”

What makes Wijnands stand out is his willingness to listen to others and collaborate

ING has already joined with four other banks – BBVA, BNP Paribas, Société General and Standard Chartered – to determine common protocols for aligning their lending with the Paris goals. Wijnands is confident other major banks will soon also sign up to the Katowice Commitment, a reference to the Polish city that hosted the latest UN climate summit and the setting for the alliance’s announcement.

Disruptors are often cast as folk who buck the trend. ING’s sustainability head certainly has no problem saying what he thinks and carving his own path. But what really makes him stand out is his willingness to listen to others and collaborate.

Reclaiming land from the sea to create towns like Almere took collective effort. As Wijnands points out, orientating the world of finance onto a climate-friendly footing will require precisely the same.

CV: Leon Wijnands

Global head of sustainability, ING

2013 -

Director sales and service Call, ING

2010-2013

Director customer intelligence, ING

2007-2010

Director product management retail products, ING

2003-2007

Call centre manager, Postbank

2001-2003

Marketing savings manger, Postbank

1999-2000

Head of marketing, planning and control for mid-corporates, ING

1997-1999

ING's Leon Wijnands will be one of more than 150 speakers at the 18th annual Responsible Business Summit Europe 10-12 June in London.

Main picture credit: ING