Phil Bloomer of the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre assesses the results of the 2018 Corporate Human Rights Benchmark and finds that while there has been welcome progress among a small group of leaders, the vast majority of companies are content to under-perform

The first full version of the Corporate Human Rights Benchmark is published today, with key findings on companies in the apparel, agricultural products and extractives sectors. The results reveal that there is a race to the top in business and human rights performance, but only amongst a welcome cluster of leaders. The great majority have barely left the starting line, with 40 of the 101 companies surveyed failing to show any evidence of identifying or mitigating human rights issues in their supply chains.

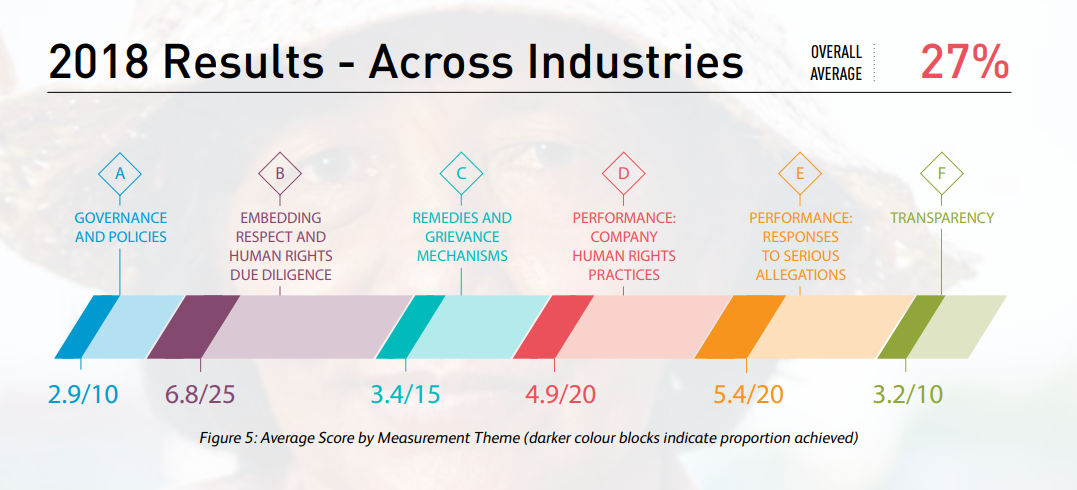

CHRB measures how companies perform across 100 indicators based on the UN Guiding Principles on Human Rights. It uses publicly available information on issues such as forced labour, protecting human rights activists and the living wage to give companies a maximum possible score of up to 100%. In this year’s ranking, two-thirds of companies scored less than 30% overall. However, members of the small leadership group from the 2017 Pilot Benchmark have continued to compete to be the “best in class”, and each has made progress to ensure they do not fall behind direct competitors.

The alignment of purchasing with human rights is not easy, but without, abuse in supply chains is inevitable

These could soon be joined by some fast improvers that have acted decisively to improve in the last year. There were alarmingly low scores in some areas of systemic challenge, which serves to highlight how far business has to go. The alignment of purchasing practices with human rights is not easy, but without this, in food and apparel, abuse in their complex global supply chains is inevitable. Very low average scores were also recorded for commitments to living wages, which are fundamental to achieving a decent life, especially for women workers; and policies to protect increasingly threatened human rights defenders in supply chains, whose work is vital to uncover abuse and dangers for both communities and workers.

In each there were only brave outliers that refused to put systemic action to eliminate the worst human rights risks, such as modern slavery, poverty wages, and violence against whistle-blowers, in the “too-difficult box”. This reflects, anecdotally, what we at the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre have seen more broadly across the high-risk sectors, and we see this pattern replicated in other robust benchmarks, including KnowTheChain and Ranking Digital Rights: There is a refreshing but small leadership group demonstrating that respect for human rights is a moral imperative, and commercially viable.

The most challenging news from this benchmark is the lack of significant progress on last year by the majority. There is an unacceptably large group of companies who are not doing enough and appear content to hide in the pack of under-performers. While it is hardly surprising that those companies with no significant record of taking human rights seriously have been the slowest movers since 2017, we are encouraged by what is happening around them that is likely to quicken their pace over coming years.

First, leading companies are beginning to gain greater access to cheaper capital, based on their lower human rights risks. The fact that sustainable investment funds have effectively doubled in size each year since 2012 demonstrates the growing appetite for companies that manage their environmental and social risks. And this year Danone successfully pioneered a $300m social bond that attracted investors focused on ESG risks.

Good practice by companies emboldens timid governments to raise the minimum floor of corporate behaviour

Second, faced with the collapse of public trust in global markets, governments are beginning to exert themselves with increasingly bold steps toward regulation for mandatory transparency and due diligence. Good practice by leading companies emboldens timid governments to raise the minimum floor of corporate behaviour through regulation and incentives. This should be welcomed as it outlaws the reckless cowboys in every high-risk sector.

Third, we see civil society and investors using the results of the benchmarks to exert pressure on laggard companies and recently a number of investors have teamed up, privately, with campaign groups to ensure that harder-hitting shareholder resolutions are raised at the AGMs. These pressures look set to grow and spread over the coming years. This is essential.

With humankind facing extraordinary transitions – to zero-carbon economies, to automation and gig economies, to mass migration, all amidst the challenges to democracy and open societies – the Corporate Human Rights Benchmark will be one key assessment to press companies to play their full role in helping create a more sustainable and prosperous future for all. Equally our association now with the World Benchmarking Alliance will ensure that human rights in business is unavoidable if companies want their operations to be recognised as playing a part in delivering the Sustainable Development Goals.

Phil Bloomer is executive director of the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre and member of the advisory council for the Corporate Human Rights Benchmark

CHRB UN Guilding Principles on Human Rights mining apparel agriculture