The issue of global inequality is suddenly a global hot potato. Do companies have a meaningful contribution to make to a more equitable future world?

When the World Economic Forum decided that income inequality was the top trend in its 2015 trends report, the issue was already heating up.

Income inequality, which has been building in the developed nations for decades and is also a feature in the developing world, hasn’t as a rule captured the attention of the media, however. Though it shapes our lives in numerous ways, it’s a topic that is vastly complex and intrinsically, somewhat yawn-producing.

US president Barack Obama said inequality was the “defining challenge of our time” in his January 2015 State of the Union Speech – the reaction was brief. In the UK, though Labour leader Ed Miliband talks about closing the tax loopholes that favour richer citizens, addressing income and wealth equality is not openly addressed. Yet, importantly, wage protests growing in the US and in Scotland may indicate that regular citizens are beginning to realise their situation isn’t getting better, though economies have.

Although income inequality is nearly wholly a result of our capitalist market systems and structures, it is generally considered an issue for governments to deal with. Data from US thinktank the Pew Center shows that people tend to believe that governments are more responsible than businesses for inequality and for solutions to make amends. Companies and entrepreneurial activity are considered more the panacea, driving growth that will act, as former US president John F Kennedy once put it, as “a rising tide to lift all boats”.

Uber inequality

Unless global inequality is checked, Oxfam says, the wealth of the richest 1% of people will overtake that of the 99% next year.

The 1% are “uber consumers”. Richer people accounted for about 55% of the increase in consumption between 1993 and 2003, and 71% of the increase between 2003 and 2013.

Source: Oxfam

The leaky boat

Unfortunately, the history of the past few decades shows that exactly the opposite has happened in developed countries, and if China is an indication, will happen to developing nations as well. Just in the past five years, from 2009 to 2014, the share of global wealth owned by the top 1% richest people rose from 44% to 48%. Even more disturbing, according to analyst Pavlina Tcherneva of US thinktank the Levy Institute, in each economic expansion since the Second World War, smaller and smaller shares of the gains in income growth have gone to the bottom 90% of families.

“The inequality issue is a complex one – there’s not a single cause. We have a ‘financialised’ economy taking a larger share of profits, and labour markets tied to financial markets,” Tcherneva says. “One consequence is that when markets falter, governments’ response is to stabilize financial markets first.”

Tcherneva says governments have let the idea of pressing for full employment fall by the wayside and accepted “jobless” recoveries (in which a macroeconomy grows with stagnant or decreasing employment) as normal.

She says the private economy may be losing steam as an engine of job growth, though, because firms are not hiring as much as they could, which eventually leads to not enough “vending” of goods and services and the creation of a vicious cycle. What is needed, she says, is a new “New Deal” [the economic programmes enacted between 1933 and 1938 to break staggering US unemployment] that looks to full employment as another engine of economic growth. “Has this idea matured in the minds of global leaders?” Tcherneva laughs. “Maybe not yet, but the time has come.”

Thomas Piketty postulates in his best-selling 2013 book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, that extreme inequality could be coming our way as the returns on capital exceed actual economic growth. Subsequently analysts have put forward suggestions on how to rebalance global wealth and income – Piketty says a global progressive wealth tax is needed. There really aren’t that many other possibilities: redistribution; rejigging taxes; more social welfare policies; universal free education.

And then there’s business. Of course, the growth of social enterprises and B Corps expressly take on the idea of business for good. Now, new voices are hinting that corporate social responsibility – integrated throughout the value chain – can contribute to more equitable societies.

Paul Tudor Jones, a hedge fund manager and billionaire, believes business must drive better income and wealth equality. Tudor Jones says he’s afraid that if companies don’t reform, societies are headed to revolution, higher taxes, or wars – and none of those options appeals to him. Tudor Jones has funded a new non-profit initiative called Just Capital. He says that increasing justice in corporate behaviour is the only way to use the current capitalist system to reduce inequality.

Martin Whitaker, chief executive of Just Capital, says “justice” is, of course, a hard concept to pin down – thus Just Capital’s first step is surveying 20,000 people to get a representative view of what the public thinks companies should do to foster more equitable societies.

“We think the public’s is both a voice that hasn’t been heard and also a voice that has a surprising depth of intelligence,” Whittaker says. “People understand that there will be real-world trade-offs, but they also understand that the current set of market signals are not strong enough to create a better system.”

Most of the surveys are completed. In September Just Capital will release its data as it also begins to index the top 1,000 public companies using the public’s criteria for just corporate behaviour. Whittaker says actions such as Unilever’s to become a B Corp are indicative that some company leaders have become aware of the necessity for business to address social well-being and equality issues.

“I don’t think any initiatives within the CSR and sustainability movements have caught the popular imagination. What we are doing collectively isn’t enough to address the systemic issues,” he says. “At Just Capital we are not trying to pile on another set of standards. We do want to redefine the framing of how companies should and shouldn’t behave. In the end our success will depend on whether we can start a genuine movement and enough of a groundswell that people take notice.” Just Capital’s index is set to appear in September 2016.

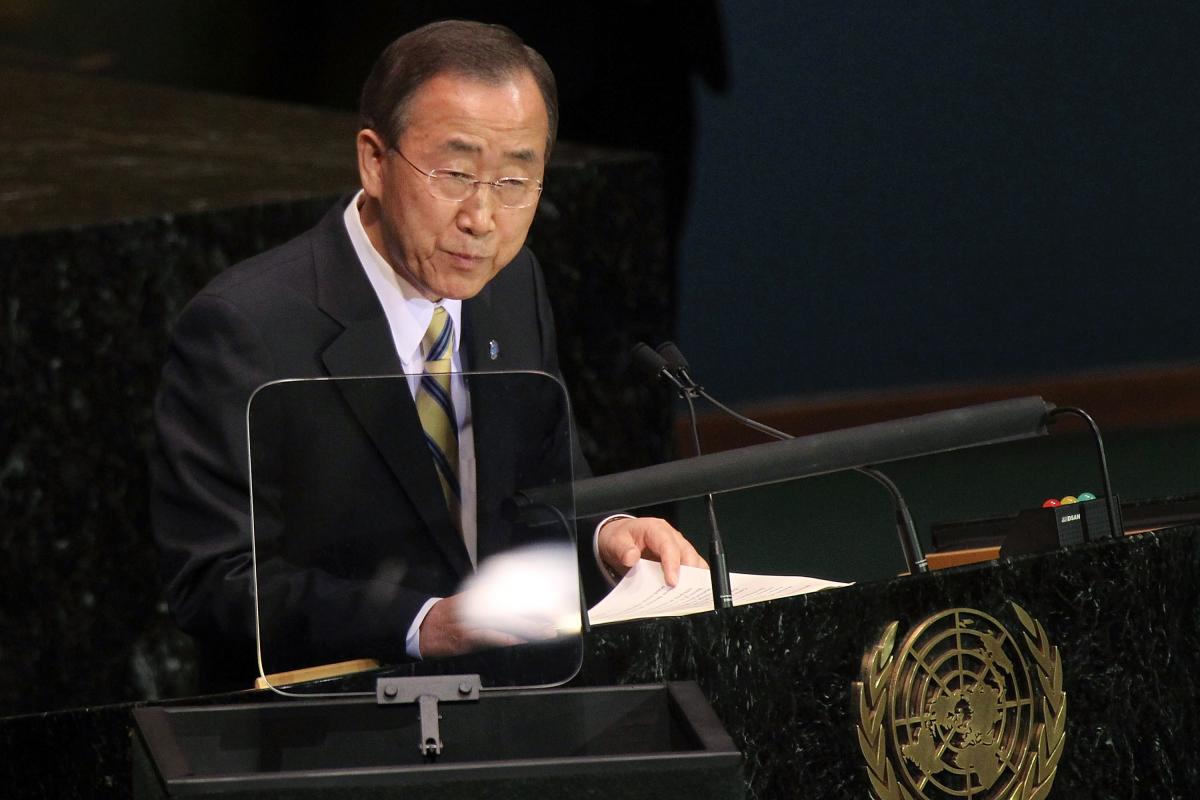

In the meantime, the United Nations has also realised the need for public companies to take a bigger role in rebalancing economic equality. Laura Asiala, a consultant at non-profit Pyxera Global, says large companies are embracing the “shared value” perspective that has popped up in sustainability circles. Asiala says the fact that the UN has renamed and reformulated Millennium Development Goals (MDSs) as Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and solicited the input and participation of the private sector is hugely significant.

“From a corporate standpoint I don’t think all that many of us heard about the MDGs or knew what they were,” Asiala says. “This time around the UN has done an awesome job of reaching out and that has coalesced into the Impact2030 effort.” Impact2030 mobilises corporate volunteers to transfer skills and resources where they are most needed globally.

Companies such as Google, IBM, UPS and Ritz-Carlton have already joined the new initiative. Critics say the Impact2030 effort will not affect the fundamental systemic drivers of inequality, but Asiala says it is part of getting business deeply involved in the SDGs. “We can recognise that companies have their own agendas and subgoals but that they aren’t mutually exclusive to the main SDG objectives,” she says.

Health impacts

Income inequality is bad for your health, says a new University of Wisconsin study, which found people in areas of income inequality more likely to die before the age of 75 than those in more equal communities. Researchers speculate this phenomenon holds true between countries, and that in communities where wealthier inhabitants can buy their way out of social service need there is less cohesion, less investment in public goods, and more stress.

Public problem, private solutions

While Just Capital may help define what public companies should be doing to correct inequality, other solutions for private companies are also coming to the fore.

There’s been a rise in popularity of worker-owned cooperatives. Trebor Scholz, a professor at the New School in New York says the cooperative business model is one way to counteract the lack of concern and equitable pay structures and benefit systems for the working people at new-style “sharing economy businesses” such as Uber and Handy. Worker-owned co-operatives, Scholz says, can be successful in the high-tech and other digital industries – he mentions Fairmondo, a co-operative version of E-Bay, and TechCollective, a worker-owned San Francisco tech support cooperative.

Mary Josephs, founder of Verit Advisors, an investment banking consultancy in Philadelphia, thinks there’s another way. She sees Employee Stock Ownership Plans (Esops) as a new method of corporate ownership for US companies.

Josephs says Esops should be better known as a way for entrepreneurs and business owners – who drive innovation and solutions to problems – to correct some of the inequalities in current business structures and still give owners a way to get liquidity without private equity. Josephs says the data already clearly shows that Esops perform better. “Esop employees are owners – they tend to work harder, more collaboratively, and share productive ideas more freely,” she says.

About 7,000 Esop companies exist today, and Josephs says they are becoming a way to increase employee retirement savings (workers receive company stock as a benefit) as well as create balance and equitable companies where all workers are owners. “Executives have appropriate compensation and employees do, too,” she says.

Clif Bar, the successful US-based sports food manufacturer, Josephs says, is one of the best examples of a company that embraces the traditional definitions of economic and environmental sustainability and, through an Esop structure, has found a way to provide social sustainability for employees.

Though inequality is a tough issue for companies to tackle, with the rise of millennials as the dominant, younger sector in the work force, perhaps novel ideas for how to balance and spread growth among a greater percentage of people will come faster. In Seattle, local business owner Dan Price caused a blizzard of interest when in mid-April he announced that all of the 120 employees of his successful credit card processing company Gravity Payments were going to receive a $70,000 salary in 2015 – including himself.

After reading about growing global inequality as well as about how much money it takes for the average human to be happy, Price decided that his own $1m salary could stand a massive cut while he boosted the wages of a majority of the staff (the average pay before the announcement was $48,000). Price has committed to at least a three-year experiment for this new minimum company wage.

And despite the critics saying that Gravity has made itself uncompetitive, Price has said that the move is in line with the company’s goals. He also says that the current situation of inequality is simply a symptom of companies’ inability to self-regulate. “When I look at Gravity’s success, it comes from the fact that we are out there serving others. That’s our ethos. That’s who we are. What’s cool is being happy, and serving others and caring about others, and all of these things go along with true success.”

Emerging equality

Social tensions over rising inequality in places as diverse as Hong Kong, Singapore and South Africa have precipitated new government measures – in Singapore a raising of the top income-tax rate; in South Africa an across-the-board tax rate rise except for the lowest income earners; and in Hong Kong new benefit programmes for the elderly and poor.

Source: Bloomberg

Welfare bonus

Income inequality continues to spark controversy about executive pay. A recent study from the Haas School of Business, University of California, Berkeley, found that restrictions on executive compensation can benefit shareholders and enhance social welfare.