With one billion people globally lacking access to cooling, the city's plan to protect even its poorest residents from frequent heat waves has been replicated across India. Diana Rojas reports

Despite the attention being given to corporate and governmental efforts to making future cooling more efficient and eco-friendly, a startling fact often gets overlooked: while the 30 hottest cities are in developing countries, far less than one per cent of development aid goes to help countries implement cooling strategies.

The result: more than one billion people lack access to cooling (and in many cases, the electricity to power it), with an ever-increasing threat of heat-related deaths in urban slums. It also means that the rural poor and farmers lack access to cold chains to keep food safe and nutritious, and health systems have difficulty keeping vaccines and other medicines viable. And, not inconsequentially, more than two billion others in the growing middle classes can only afford high carbon, less-efficient cooling equipment, which will lead to a spike in global climate change, according to a 2018 report by Sustainable Energy for All (SEforAll).

Globally, if air conditioning were to be made available to all who need it, and not just those who can currently afford it, the number of units would need to rise from 3.6 million today to 14 billion by 2050, according to a UN report.

We see resource-limited families stretch to procure an air conditioner, but then realise they cannot afford to operate it

“The shame of it is that we see resource-limited families stretch to procure an air conditioner so that they can finally sleep well at night, but then realise that they cannot afford to operate this life-enhancing appliance as it consumes so much electricity, proving to be a burden on their pockets,” said Iain Campbell, senior fellow at the Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI), which is sponsoring the Global Cooling Prize. (See Can we defuse the 'ticking time bomb' of soaring demand for cooling?)

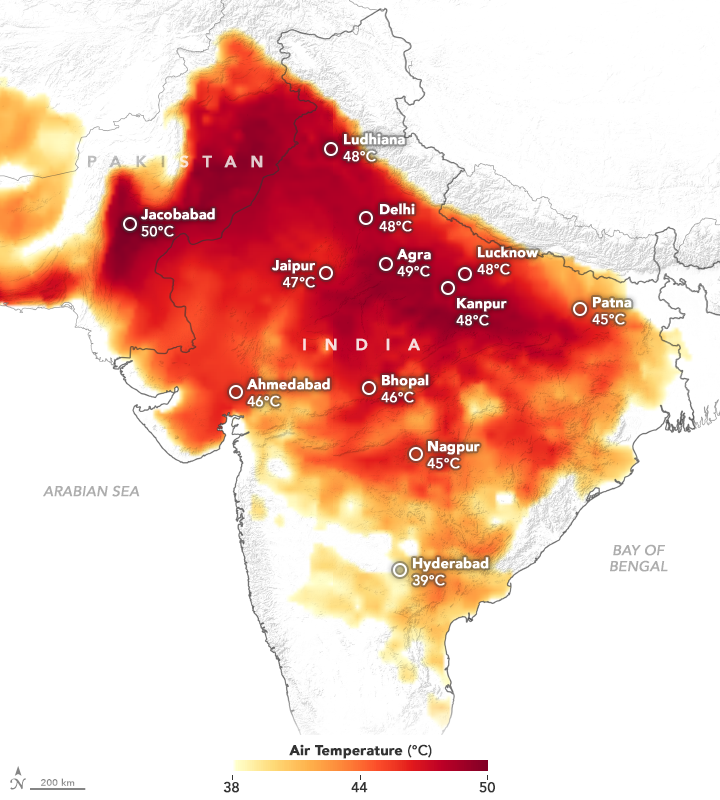

With 30% of the global population already facing dangerously high temperatures more than 20 days a year, heatwaves are causing some 12,000 deaths annually, and that fatality rate is expected to rise to 255,000 by 2050, according to the SEforAll report. In 2015 in India and Pakistan alone, some 4,500 people died during a heatwave that saw temperatures rise to an unfathomable 49C.

The Kigali Cooling Efficiency Program (K-CEP) notes that access to cooling is needed to achieve a number of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, such as ending hunger, disease and poverty. Studies have shown that worker productivity declines as the heat rises above the 20-30 degree threshold, and that heat in the classroom is tied to educational performance in children. And with the changing climate, diseases that previously were only common in tropical zones will spread, making the need for cooling to preserve vaccines more urgent.

Yet despite the bleak reports, ideas abound to help cool humans while not further heating up the globe. These range from off-grid solar systems to support fans and cold-chain refrigeration, to instituting more low-cost passive cooling – cool and/or green roofs, building design and retrofit to allow for better cross-air flow – as well as financing instruments to help with the purchase of energy-efficient cooling equipment.

After 1,300 people in Ahmedabad, in western India, died in a heatwave in 2010, the city of 6.4 million people decided to act to try to minimise future loss of life. Working with the Indian Institute of Public Health, the US-based Natural Resources Defense Council, other groups and NGOs, and municipal leaders brought in South Asia’s first heat action plan.

An early warning system is in place to alert those most a risk when temperatures above 45C are imminent, including grassroots workers dispatched to areas where the most vulnerable people are living. During times of red alerts, school timings are changed, water is distributed to all bus depots, power cuts are banned, and hospitals are mobilised to treat heat-related illnesses. The city has also brought in cool roofs across the city, claiming that this brings down inside temperatures by 5-7C.

The initiative has been so effective that 30 cities in 11 other Indian states have since adopted similar plans.

This article is part of our in-depth Climate-resilient cities briefing. See also:

Can we defuse the ‘ticking time bomb’ of soaring demand for cooling?

From urban farming to green homes: the US cities building climate resilience

Hermosillo and Belo Horizonte make CDP A grade as two of Latin America’s greenest cities

UK cities ramp up action to boost resilience, with double of number on CDP climate A list

SEforALL NRDC Rocky Mountain Institute K-CEP SDG7