Katinka C van Cranenburgh proposes a new business model based on the SDGs to help brands deal with the demands by activists

Grassroots organisations and NGOs have a long history of pressuring multinational corporations into increasing respect for human rights. But sometimes the companies that take the lead in cleaning up their acts find themselves targeted by even more social activism, demanding more change.

That is what I discovered in my case study on Heineken’s efforts to improve conditions for so-called “beer promoters” in Cambodia when doing my PhD at the Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University.

Social activism, especially when played out in the media, is a powerful method to push corporations towards better working conditions or better care for the environment. But dealing with social activists in small, flexible organisations that can change strategies on short notice does not always come intuitively for multinational corporations, which operate with long-term plans for social responsibility.

As a former Heineken executive, I wanted to find out how managers of the brewer reacted to social pressure from a local NGO that tried to improve working conditions for the beer promoters in Cambodia.

At the time of my study, most Cambodian bars did not have bartenders, but used female beer promoters to sell beer to their mostly male clients. The beer promoters, who were employed by local subsidiaries of global beer brands, typically welcome the guest and try to sell them beer of one particular brand. As such they were part of Heineken’s marketing strategy in the country.

In 2000 a few local NGOs drew attention to the spread of HIV in Cambodia, including among what they called “indirect sex-workers”, such as beer promoters. One NGO, Sirchesi, told the media that beer promoters were pressured by male clients to sit down and drink alcohol in exchange for tips. Most beer promoters found this difficult to resist because of the highly competitive working environment. The NGO also said that beer promoters were being underpaid by the major international beer companies.

Social pressure and responding to criticism

When Heineken learned about the pressure from the organisation, it first asked its local partners, the employers of the beer promoters, to respond. They said the working environment for beer promoters was not “unusual or problematic” in Cambodia. But Heineken global headquarters felt the need to respond, even though it did not directly hire the beer promoters. Heineken launched a programme aimed at creating safer workplaces by training and informing the beer promoters about dealing with harassment and other risks on the job. The company also installed female supervisors and provided them with health insurance.

Heineken’s efforts improved the job safety for the brand’s beer promoters significantly. But 4,000 women who promoted other beer brands did not see any improvement. The activist NGO took notice and stepped up its demands on Heineken. It now wanted to see the beer promoters’ salaries doubled. It also demanded that Heineken provide free HIV/Aids treatment to its workers, although those treatments were already free in Cambodia.

Seeking alliances

In response, Heineken decided to form an alliance with other breweries that used beer promoters in Cambodia, hoping to reduce job risks for beer promoters across the entire industry. Only two other breweries joined: Carlsberg and Diageo.

Other breweries said they were committed to the cause, but were afraid that joining the alliance would raise their public profile, and make them the focal point of NGO action. Heineken’s earlier work to improve conditions for HIV/Aids patients in Africa had also made the company more visible – and vulnerable – to media exposure generated by NGOs. The standards to which they could be held accountable were higher because of their earlier successful policies.

After documenting this case, I conclude that Heineken and the NGO never managed to converge on finding solutions. Heineken’s managerial responses were motivated by their global policies and corporate values and identity. This made the company willing to improve worker conditions. But complying with all the activists’ demands did not make sense for Heineken, which said the wages for beer promoters were competitive, and HIV treatments were already widely and freely available in the country.

This case also shows that activist organisations can become “entrenched” in their own activism. Their identities become shaped by opposition to corporate policies rather than constructively supporting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). As such theyhave a stake in perpetuating the problem, rather than ending it. Their ad hoc approach and sometimes quickly shifting demands can complicate a company’s efforts to build good relations with NGOs.

New model based on the SDGs

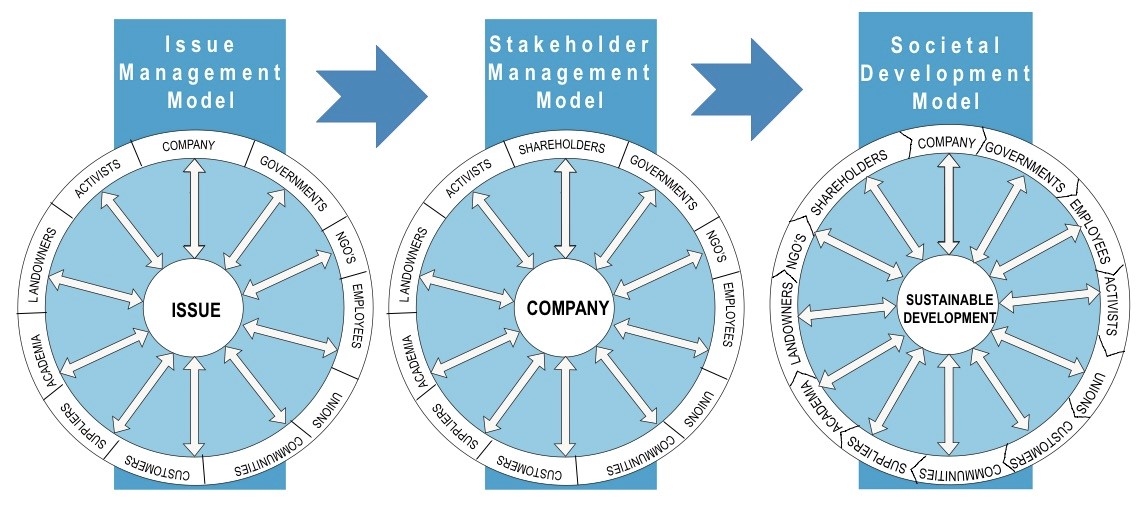

As a solution I propose that businesses shift from the traditional stakeholder model to a new model of corporate responsibility that puts sustainable development, or the SDGs, at the heart of managerial decision making. In this model the company is just one of the stakeholders that contributes to the SDGs in a certain area, and together with other stakeholders they form the spokes that keep the sustainable development wheel spinning.

How does this differ from the stakeholder and issue-management models?

In the stakeholder model, the company is at the centre and business managers regard other civil society actors from the perspective of how they relate to the company.

In the issue-management model a certain issue related to the business is at the centre of the model and decision-making is focused on how to best mitigate business risks. The problem with this model is that issues cannot be approached in isolation as they are interrelated, and managers trying to focus on single issues run into complexities that can turn strategies into purely theoretical exercises.

The sustainable societal model stimulates a more holistic and continuous management approach in which sustainable development is always at the centre of attention and the company is one of numerous civil society actors

What it takes

To enable businesses to have a societal approach, there is a need for them to participate in sustainable societal development on a continuous basis. This means businesses do not only engage with civil society when there is an issue at hand or when approached by an activist, NGO or governmental institution. The company, as a civil society actor, participates in development on a permanent basis.

For businesses to engage in development, there is a need for multi-stakeholder forums. If these forums do not exist, businesses will have to help create and develop them. This means they may have to take a more active role at first but will be an equal partner in a multi-stakeholder forum when it is up and running.

Activist organisations do not automatically disappear when businesses follow the societal model. As Heineken found in Cambodia, extreme or disproportional expectations may continue to reach business managers. However, embracing the societal model will make businesses less vulnerable to social activists. Instead of responding directly to the Cambodian NGO’s demands, Heineken would have been able to refer those demands to a multi-stakeholder fora. No more conflict and the winner is societal development.

Dr. Katinka C. van Cranenburgh is former Heineken executive. In 2014 she co-founded 'Community Wisdom Partners', a social performance consultancy organisation. www.communitywisdompartners.com - katinka@communitywisdompartners.com