In all countries of south Asia, reducing poverty and hunger, providing clean water and sanitation, meeting growing energy needs and adapting to climate change are at the heart of sustainability efforts

South Asia has never been a coherent political entity, though geographically it has clear boundaries: the Himalayas to the north and the Indian Ocean to the south. Former British colonies – Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh – form south Asia’s core.

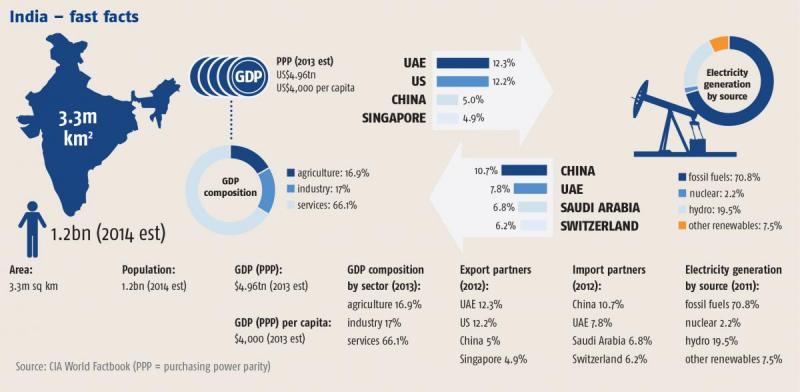

Though these four are in highly different stages of development, and giant India (now the world’s third largest economy according to the International Comparison Programme) dwarfs the other three, they have certain challenges in common.

South Asia is still the poorest region in the world after sub-Saharan Africa. Hunger rates continue to be high in the region (alongside the emergence in India of a prosperous middle class). In fact, the UN Millennium Development Goals, especially those on poverty, hunger, clean water and sanitation, are challenges the region as a whole is only beginning to make headway on.

A prominent issue in south Asia is the role and the rights of women. Women’s rights, and the lack of them, are increasingly seen as centrally important to achieving economic and social prosperity, and this is reflected in the types of programmes and initiatives designed by both companies and organisations.

Add in climate change adaptation and escalating energy needs, and the challenge of sustainable development in the region is clear.

And rapid economic growth, as seen in parts of south Asia, brings its own risks, according to the South Asian Network for Development and Environmental Economics (Sandee).

“If we are not careful about how we develop, not wise about how we develop,” says Priya Shyamsundar, Sandee’s director, “the benefits of the high growth rates some of our countries have been experiencing over the last decade will be eroded as a result of not worrying about the environment.”

Indian issues

India is a huge land of strong contrasts: a thriving multiparty democracy yet lingering problems with corruption; strong multinationals with sophisticated sustainability spending alongside millions of small and medium enterprises without the means to begin sustainability work. Thus far, India has tended to embrace development on the western resource-intensive model rather than a homegrown model.

“This western model is based on rules and enforcement and now everyone believes that is the only way forward,” says Devdutt Pattanaik, an Indian leadership consultant and “chief belief officer” for the Future Group, a large retailer. “India has failed with socialism so I guess [there’s] no harm in trying this new model out, since everyone has forgotten our old models. But will these models also work in overpopulated, poor, highly fragmented old social structures that were colonised?”

One recent innovative approach builds on existing cultural practices. Mumbai’s famous “dabbawalas” ride bicycles and motorcycles to ferry hundreds of thousands of lunches to office workers each day. Advertising agency McCann Mumbai and the NGO Happy Life Welfare, representing Mumbai’s union-like Dabbawala Foundation, came up with a unique programme to share untouched, uneaten portions of workers’ lunches with Mumbai’s hungry children.

Office eaters put a Share my Dabba sticker on their stacked, round lunch boxes, and those get separated and redistributed to hungry children. The programme costs little to run (though needs precision timing to intersect with busy dabbawala schedules), alleviates the effects of poverty and keeps food waste down.

A uniquely Indian solution, Share My Dabba is the type of community-development business initiative that Australian businessman Murray Hunter is trying to propagate, as he says it will help south Asia address outdated industrial approaches to business.

Solutions such as this, Hunter says, allow people to help sustain others through their own activities and provide one alternative to massive multinationals controlling the supply chains that urban places such as Mumbai rely upon.

But with the advent of new Indian sustainability legislation – mandating that from April 2014 large corporations devote 2% of profits to sustainability – there will be even more of a shift to western models. As many as 16,000 Indian companies may meet the definitions of “large corporation” set by the government. This group, which includes the Indian mega-corporations Tata, Airtel, Reliance and Wipro, will generate an estimated $2-3bn annually for sustainability in the country, and this legislated sustainability spending is sure to causes ripples throughout the region.

Pakistan’s problems

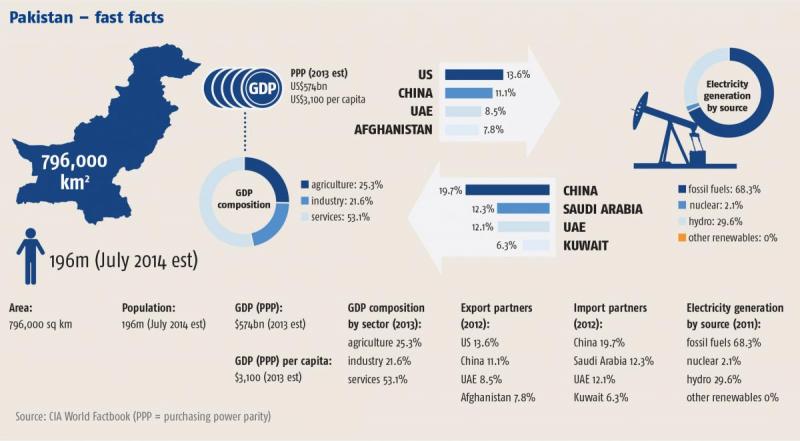

Pakistan can sometimes seem like India’s poor relation, including in the realm of sustainability efforts. There is still extremist violence in this nation of 180 million people, high hunger rates, and nearly half the country lacks access to clean water. Pakistan is also among the worst places to be a mother, in terms of maternal and child mortality, ranked 147th of 187 countries globally by a new Save the Children report. Child labour is a major problem, with 3.3 million children below the age of 14 working instead of going to school, according to the government’s own reports.

Mainstream financial firms such as Morgan Stanley see Pakistan as an exciting prospect in 2014, because of the newly elected government’s aggressive economic initiatives and the underlying capacity for growth.

Norwegian telecom firm Telenor, for example, has achieved significant first quarter 2014 growth in Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh, with the company reporting 5.9m new customers in these three countries in this period. Yet Pakistan has failed to put safeguards in place to control rampant environmental degradation, says the World Bank, with the burden of this falling more on the country’s poor as they are most exposed to such environmental problems.

Pakistan’s social responsibility performance is also having negative economic consequences. US entertainment giant Walt Disney, for example, in April 2014 cut Pakistan from its list of approved importer companies because of “poor governance standards” in the country. And the recent experience of Finnish forestry company Store Enso details the complexities and reputational risk associated with doing business in Pakistan.

Pakistan’s water problems are pressing, as shortages and drought in the Tharparkar region in early 2014 demonstrate. The country has only 30 days of water reserves, a crucial lack in a country where agriculture accounts for more than 20% of GDP.

Yet while global observers are deeply concerned about Pakistan’s water supplies, sustainable solutions have not yet emerged domestically. Tensions with India and neighbouring Afghanistan on water rights further complicate the issue.

Overall, Pakistani companies have a philanthropic tradition with Islamic roots, but corporate sustainability activity is not widely integrated in companies’ core work.

Fine, a Pakistani telecommunications company, as well as the multinationals UPS and Shell, have gained kudos for sustainability initiatives, though they lean more towards philanthropy. In energy, the microfinance NGO Buksh Foundation facilitates alternative energy financing at the grassroots with projects such as the Solar Lanterns initiative. Pakistan also has a well-developed banking sector and is developing its Islamic banking and loans, and the financial sector may drive sustainability reporting and initiatives in the future.

Sri Lanka’s success

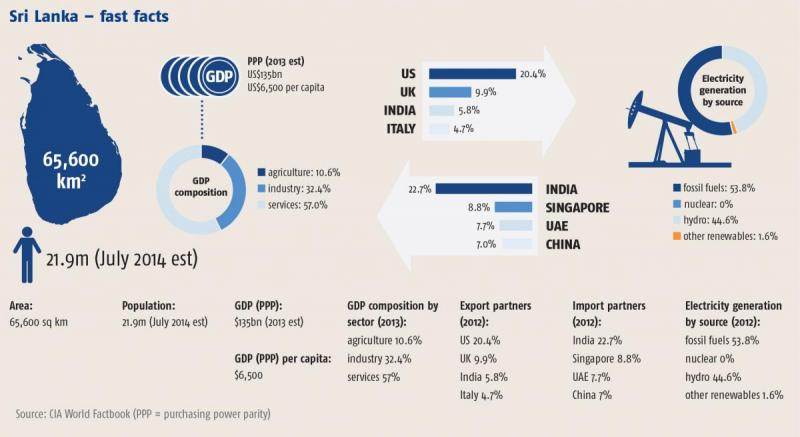

Sri Lanka is Asia’s oldest democracy, and this island nation of 20 million also has the highest per capita income in the south Asia region. Following two decades of civil war, which ended in 2009, the country is benefitting from a period of greater stability.

Sri Lanka formerly had a plantation economy with cinnamon, rubber and tea as key exports. Now Sri Lanka seems to be sizzling economically with estimates of annual 7.5% growth. Tourism and apparel as well as the plantation industries are all doing well. Sri Lanka will also boast one of the world’s tallest vertical gardens when its 46-storey Clearpoint Residencies building, covered in plants and with a self-sustaining watering system, is finished in 2015.

Sri Lanka is in the process of moving corporate efforts from philanthropy to sustainability. Research firm Global Insight found a high degree of philanthropic giving in a survey of 260 companies in late 2013. While most of the larger companies surveyed had formal philanthropy or sustainability programming, only a handful had any method of evaluating the impact of these activities.

An initiative by clothing company Mas Holdings may indicate that the apparel sector in Sri Lanka will lead the way in more firmly addressing core business goals and sustainability. Alarmed at the ramifications of thousands of young women having to leave rural areas for urban (mostly apparel) jobs in Sri Lanka, Mas has begun building factories away from cities in rural regions so that the mostly female workforce can stay nearer their homes and families.

Water and the effects of climate change on the annual monsoon are important issues in Sri Lanka, a country prone to drought. The government, which has cracked down hard on protests about access to clean water, is currently developing a new water policy to try to deal with competition for water between companies, farmers and growing urban areas.

Rainwater harvesting is emerging as an “old-is-new-again” solution that could help – there is even national legislation specifying that some roof areas be designated for harvesting systems. Rainwater harvesting is developing in a new guise as a disaster risk reduction tool and a bulwark against climate change. A campaign to raise awareness of the practice, and provide loans for low-cost rainwater systems, is being tested in parts of Sri Lanka this year, funded by USAid and the non-profit Lanka Rainwater Harvesting Forum.

Bangladeshi boom

Bangladesh is on track to meet the Millennium Development Goal of halving extreme poverty by 2015, compared with 1990 levels. On social indicators, Bangladesh has outperformed its south Asian neighbours in life expectancy (except for Nepal) and in lower infant mortality rates (for under five year-olds).

While climate change is a major concern for such a low-lying country, Bangladesh has huge future aspirations – it intends to be a middle-income country by 2021. With its innovations – the country pioneered microfinance and is good at educating females and spurring their presence in business sectors – it may well achieve these goals, though in uniquely Bangladeshi ways (see case study page 23).

A key current challenge for Bangladesh is to continue to grow economically while rebuilding the image of the ready-made garment industry after the tragedy of Rana Plaza. Other major challenges remain: continuing to erode hunger, improve health, and bring electricity to the rural population.

While it is estimated that only about 60% of Bangladeshi households have electricity through a grid connection, Bangladesh is experiencing a massive off-grid solar home adaptation rate of 50,000 households a month.

Solar homes are succeeding in Bangladesh, says World Bank south Asia energy specialist Zubair KM Sadeque, because of the strength of the Bangladesh-based financial intermediary, the Infrastructure Development Company, which receives funds from the bank and funnels them through NGOs and microcredit lenders. In addition, Sadeque says, close attention has been paid to the reliability of the components used.

While in the west, consumers rarely think about their electricity supplies, in rural south Asia the novel advent of solar homes has had major impacts. An evaluation in 2013 showed longer study hours for children, improved indoor air quality from the switch away from kerosene, and more participation from women in household decision-making. Last but not least, small villages are anecdotally safer with the advent of night-time lighting.

Overall, in south Asia, sustainability initiatives are just gradually moving away from simple philanthropy, and still take place in the context of development. As the region grows more aware of how to combine development with sustainable outcomes, that can be a positive, as shown by eye-catching successes to date.

April Streeter is an associate with One Stone. A certified B Corporation, One Stone has a global team offering sustainability consultancy and communications expertise, based in Stockholm, Edinburgh, Sydney, Portland and Washington DC.

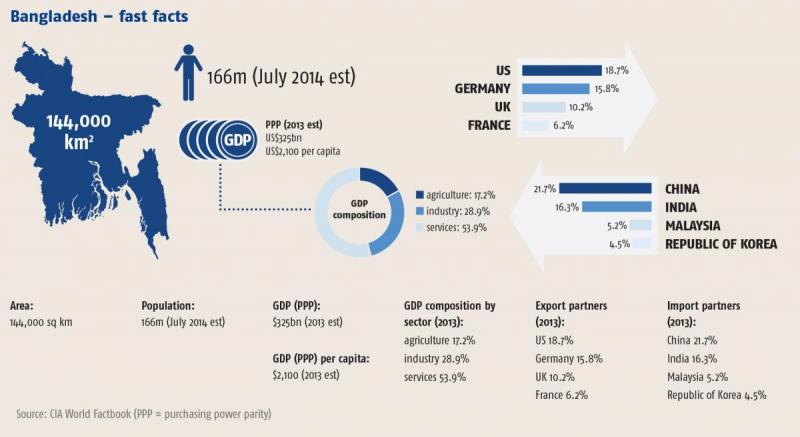

Source: CIA World Factbook (PPP = purchasing power parity)

Bangladesh global sustainability India Pakistan South Asia briefing Sri LankaMay 2015, Singapore

Ethical Corporation's Responsible Business Summit Asia is the regional prominent meeting place to find out where business leaders and innovators are headed around their sustainability and CSR strategy - so you can be a leader too.